On the whole, American workers are generally satisfied with their jobs. Even so, a significant share (30%) view the work they do as “just a job to get them by,” rather than a career or a steppingstone to a career. Views about work are sharply divided along socio-economic lines, and the sense of vulnerability is most acute among workers with no college education and lower-than-average household incomes.

There are also significant differences across industries and occupations. For example, people who work in management are more likely to be satisfied with their current job, to be in salaried positions and to have a more robust set of employer-provided benefits. By contrast, workers who are in retail, service or manual occupations have fewer benefits and lower levels of satisfaction.

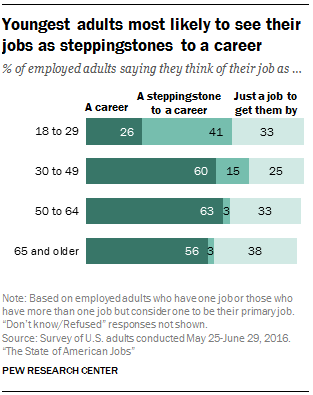

About half of U.S. workers describe their job as a career, while 18% say it is a steppingstone to a career. Three-in-ten workers say their job is “just a job to get them by.” Those who describe their job as a career tend to be at least 30 years old and well educated, with higher incomes and holding full-time, salaried jobs.

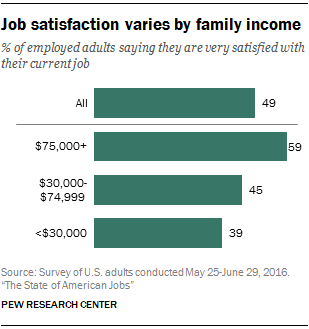

About half (49%) of American workers say they are very satisfied with their current job. Three-in-ten are somewhat satisfied, and the remainder say they are somewhat dissatisfied (9%) or very dissatisfied (6%). Job satisfaction varies by household income, education and key job characteristics. And the way people feel about their job spills over into their views of other aspects of their lives and their overall sense of happiness.

About six-in-ten (59%) of those with an annual family income of $75,000 or more say they’re very satisfied with their current job, compared with 45% of those making $30,000 to $74,999 and 39% of those making less than $30,000.

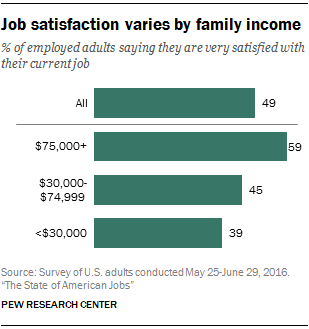

Certain types of employees are more likely to express satisfaction with their current job. People who work in management are particularly likely to say they are very satisfied (62%), compared with, for example, those who work in manual or physical labor (48%). In addition, those who work in full-time jobs (52%), salaried positions (58%) and permanent positions (53%) are particularly likely to say they are very satisfied with their current job.

When asked about their satisfaction with the kind of work they do, employed Americans with high family incomes again say they are the most satisfied (65% of those making $75,000 or more say they are very satisfied, compared with 49% of those making $30,000 to $74,999 and 51% of those making less than $30,000). Permanent, full-time and salaried employees are also more likely than their counterparts to say they are very satisfied in this area.

Similar patterns are reflected when Americans are asked about satisfaction with their family life and personal financial situation, as well as their overall happiness.

For example, about six-in-ten adults (61%) with a family income of less than $30,000 per year say they are very satisfied with their family lives, compared with eight-in-ten adults whose family income is $75,000 per year or more.

There is also a difference by education. Though 71% of Americans overall describe themselves as very satisfied with their family lives, that figure is lower among those with less than a high school education (64%) than those with at least a bachelor’s degree (75%).

About a third of Americans (32%) say they are very happy with how things are going these days in their lives, while 51% describe themselves as pretty happy and 14% say they are not too happy.

Large differences in happiness emerge when comparing those with high levels of education and income and those with low levels. For example, adults with less than a high school education are more than twice as likely as those with a bachelor’s degree or more education to say they are not too happy with their lives (23% vs. 9%). 24 And those with low family incomes, of less than $30,000 annually, are three times as likely as those with family incomes of $75,000 or more to say they are not too happy (21% vs. 7%).

Those who are unemployed and looking for work are less happy with their lives, even when controlling for family income. Unemployed Americans who are looking for work and report a family income of less than $30,000 are about twice as likely as those who are employed and report the same family income to say they are not too happy with how things are going in their lives (26% compared with 14%).

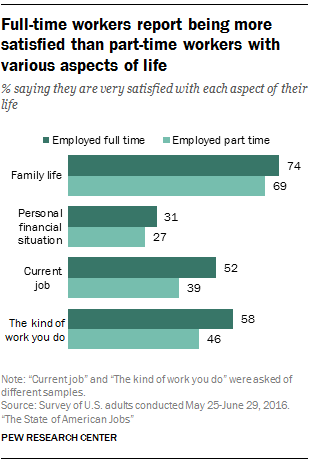

In addition to job satisfaction, the survey explored what American workers’ jobs mean to them – are their jobs central to who they are, or are they mainly just a source of income? About half (51%) of employed Americans say they get a sense of identity from their job, while the other half (47%) say their job is just what they do for a living. 25 And about half (51%) of all U.S. workers say they view their job as a career, while 18% see it as a steppingstone to a career and 30% say it’s just a job to get them by.

The same factors that underlie job satisfaction are linked to deeper attitudes about work. Workers with a postgraduate degree are the most likely to say their job gives them a sense of identity (77%), while 60% with a bachelor’s degree, 48% of those with some college education and about four-in-ten (38%) of those with a high school diploma or less say the same. Similarly, employed adults with a bachelor’s degree or more education are nearly twice as likely as those with less education to say their job is a career (70%, compared with 44% of those with some college experience and 39% of those with no college education).

Those at the top of the income scale are the most likely to see their job as part of their identity and as a career. Some 60% of those with an annual family income of $75,000 or more say they get a sense of identity from their job, compared with 37% of those with a family income of less than $30,000. And 75% of employed adults in the top income category ($75,000 or more) see their job as a career, compared with 49% of those in the middle ($30,000 to $74,999) and only 17% of those in the lowest income category (less than $30,000).

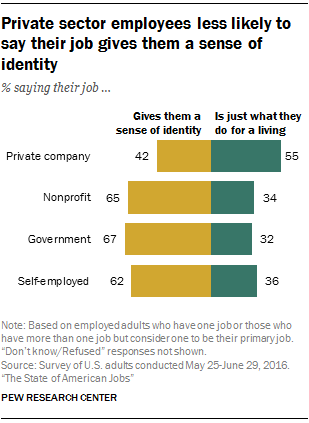

Roughly six-in-ten or more of those who are self-employed (63%) or who work for a nonprofit organization (65%) or the government (67%) say they get a sense of identity from their job, while only 42% of those who work for a private company say the same. Salaried and full-time employees are also more likely to say their job gives them a sense of identity than hourly and part-time employees, respectively.

At the same time, half or more of Americans who are self-employed (63%) or who work for a nonprofit organization (56%) or the government (66%) see their job as a career, while 44% of those who work for a private company say the same.

There are also some significant differences by industry. For example, 62% of adults working in the health care industry and 70% of those working in education say they get a sense of identity from their job, compared with 42% of people working in hospitality and 36% in retail or wholesale trade. And 66% of those working in a STEM profession or teaching say their job gives them a sense of identity, while 43% of those working in manual/physical occupations and 37% of those working in retail or service jobs say the same. 26 Employees of the same industries and occupations that are most likely to report that their job provides them with a sense of identity (health care, education and STEM/teaching) are more likely than others to say their jobs are careers.

Job characteristics are also linked to these attitudes about work. A quarter of part-time employees see their job as a career, while 22% consider it a steppingstone and 52% say it’s just a job to get them by. But among full-time workers, 58% view their job as a career, 17% say it’s a steppingstone to a career and 24% say it’s just a job to get them by.

Younger workers are significantly less likely than middle-aged and older workers to view their job as a career (26% of those ages 18 to 29) and more likely to describe it is a steppingstone to a career (41%). If this age group follows the path of older adults, many of those “steppingstone” jobs will indeed lead to careers.

Among young adults, though, there is a sharp divide by education. Those with at least a bachelor’s degree are about twice as likely as those with less education to say their job is a career (41%, compared with 21% of those with some college experience and 22% of those with a high school diploma or less). These groups with lower education are more likely to say their job is just to get them by.

The share of U.S. workers saying their job gives them a sense of identity has dropped somewhat since the question was first asked by Gallup in 1989. Then, 57% of employed adults said their job gave them a sense of identity, compared with 51% today.

Americans’ confidence in their job security remains high after reaching a low in the early 1980s. Today, 60% of employed Americans say it is not at all likely that they will lose their job or be laid off in the next 12 months. An additional 28% say it is not too likely, 7% say it is fairly likely and 5% say it is very likely.

Even so, a segment of the U.S. workforce expresses a high level of vulnerability. Among workers with less than a high school diploma, about four-in-ten (39%) say it’s very or fairly likely they may be laid off within 12 months. By comparison, only 11% of those with a high school diploma, 10% of those with some college education and 7% of those with at least a bachelor’s degree say the same.

Similarly, those in the lowest family income bracket of less than $30,000 annually are four times as likely as those with family incomes of at least $75,000 and three times as likely as those with incomes between $30,000 and $74,999 to say they’re very or fairly likely to lose their job in the next year (24% vs. 6% and 8%, respectively).

Certain types of workers are more likely to feel their jobs are insecure. For example, 23% of temporary workers say they are very or fairly likely to lose their job in the next 12 months, compared with 8% of those who describe their jobs as permanent positions.

People who work in manual or physical occupations such as maintenance workers, farmers and construction workers are more likely than those in other popular occupations to say they may be laid off in the next year (for example, 16% of these workers say they’re very or fairly likely to lose their job, compared with 8% of those working in management). Those who work in small companies of less than 50 employees (16%) are more likely than those working in larger workplaces to say they are very or fairly likely to lose their job.

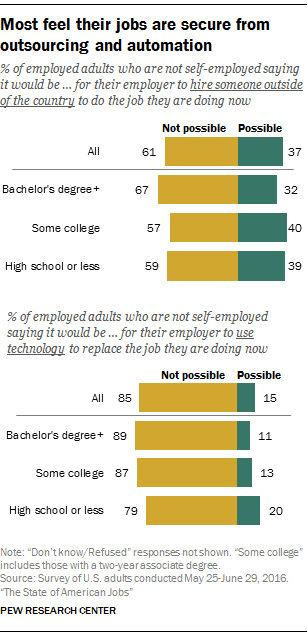

While relatively few workers say it’s likely that they will lose their job in the next 12 months, a sizable minority (37%) of those who are not self-employed say it would be possible for their employer to outsource their job to a worker outside of the U.S. This is up somewhat from 2006, when 31% believed this would be possible.

Those without a college degree and those with low family incomes are more likely to say their jobs could be outsourced. About four-in-ten workers with a high school education or less (39%) or with some college experience (40%) say this, compared with 32% of those with at least a bachelor’s degree. Workers with a low level of family income (less than $30,000) are more likely than those with family incomes of $75,000 or more to say it would be possible for their employer to replace them by hiring someone outside of the country (41% vs. 33%).

Relatively few U.S. workers believe that their jobs could be replaced with technology. Some 15% of workers who are not self-employed say their employer could use technology to replace the job they are currently doing; 85% say this wouldn’t be possible.

This is in line with previous research that found that, while 65% of adults predict that robots and computers will do much of the work currently done by humans within 50 years, 80% of workers expect that their own jobs will still exist in their current forms in the same time period.

Workers with a high school diploma or less education are more likely than those with higher levels of education to say it is possible that their jobs could be replaced with technology (20%, compared with 13% of those with some college experience and 11% of those with at least a bachelor’s degree). And those with a family income of less than $30,000 annually are more likely than those with an income of $75,000 or greater (23% vs. 9%) to say their job could potentially be replaced.

Though workers who are paid by the hour (19%) are more likely than salaried employees (9%) to say their jobs could be replaced by technology, there are no statistically significant differences between full- and part-time workers.

People who work in management professions (5%) are less likely than those in other popular occupations to say it’s possible that their job could be replaced by technology.

According to the Pew Research survey, a majority of workers report that they have access to health insurance (68%), paid sick leave or vacation (67%) and a 401(k) or other retirement program (59%) through their employer. Census data show that the share of workers with employer-provided health insurance and access to employer-sponsored retirement plans have fallen in recent decades. (See Chapter 1 for more details.)

Across the board, these benefits are more common among workers with at least a bachelor’s degree, but around half or more of workers with less education still report access to these employer-provided benefits. The youngest and oldest segments of the workforce – those who are 18 to 29 or 65 and older – are less likely to be offered each benefit.

Full-time workers are at least twice as likely as part-time workers to say that their employer offers each of these benefits to them. For example, 69% of full-time employees can access a 401(k) or other retirement program through their employer, compared with only 26% of part-time workers.

In general, those who work for the government (including federal, state and local) are the most likely to say they have access to these benefits (for example, 87% say they have access to health insurance). Private company and nonprofit employees are somewhat less likely to say their employer offers health insurance coverage (74% and 72%, respectively) and self-employed workers report a much lower rate (25%).

About four-in-ten (41%) American workers also say their employer provides tuition reimbursement for skills training or additional education. While those who are highly educated, those with high incomes, and full-time and government workers are more likely to have access to tuition reimbursement than their counterparts, 18- to 29-year-olds are just as likely to say they are offered this benefit as middle-aged workers.

These estimates of workers’ access to employer-provided benefits are similar to those found by the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Full-time and part-time workers were asked about their work schedule preferences. Full-time workers were asked if they would prefer to be working part time, and part-time workers were asked if they would prefer full-time work. For the most part, both groups are satisfied with their current schedules.

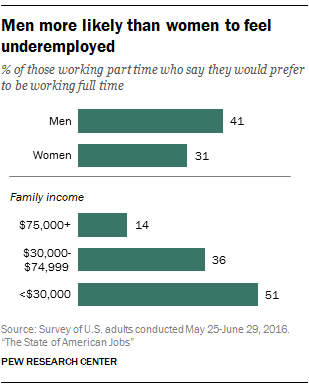

About a third of part-time workers (36%) say they would prefer to be working full time, while 64% say they would not. Men who work part time are more likely than women to say they would prefer to work full time (41% vs. 31%). Similarly, part-time working parents of children under the age of 18 living in their household are more likely than non-parents to say they would prefer to work full time (44% vs. 32%).

Among part-time workers, those with family incomes of less than $30,000 (51%) are more likely than those with higher incomes to say they would prefer to be working full time, with about half falling into this underemployed group. By contrast, 36% of part-time workers with a family income between $30,000 to $74,999 and an even smaller share (14%) among those with a family income of $75,000 or more say they would prefer a full-time job.

Most full-time workers report that they prefer that schedule (80%, compared with 20% who say they would rather work part time). There are relatively few demographic differences in this group. Women who work full time are more likely than men to say they would rather work part time (25% vs. 16%), but parents with children under the age 18 living in their household are just as likely as non-parents to say they prefer their full-time work. While those with lower family incomes are somewhat more likely to prefer part-time work than those with high incomes, there are few differences by education.

One-in-five adults who are not currently working say they are actively looking for a job. Men (23%) are more likely than women (18%) to fall into this category. And the youngest Americans are much more likely than the oldest segment of the population to be job hunting. About half (49%) of 18- to 29-year-old adults who are not employed say they’re looking for work, compared with 38% of those ages 30 to 49, 17% of those ages 50 to 64, and only 2% of those ages 65 and older. Adults who are not employed and have at least a bachelor’s degree (13%) are less likely than those with less education to be looking for work.

Fresh data delivery Saturday mornings